| |

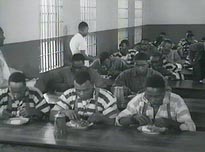

Mess hall in a segregated prison |

Prisoners of Conscience

Over six thousand COs who refused to serve in the Army and in Civilian Public Service camps, or whose drafts boards deemed them insincere, went to Federal prison. In fact, one out of every six men in U.S. prisons during World War II was a draft resister. Among them were Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam, and legendary jazz musician Sun Ra. War resisters found themselves behind bars for up to six years. Some were even held up to two years after the war ended.

Imprisoned draft resisters represented a broad spectrum of Americans. While over 75 percent of those imprisoned were Jehovah's Witnesses, members of traditional peace churches were joined by other Protestants, Catholics, Jews, socialists and anarchists. Large numbers of Puerto Ricans refused draft induction to protest Puerto Rico's colonial status. Many Hopi Indians, who are traditionally pacifists, refused the draft call.

Seventy-three Japanese American internees refused draft orders from the

Heart Mountain relocation camp in Wyoming to protest the internment of Japanese-Americans. They were imprisoned for their action.

CO prisoners were threatened by fellow inmates and guards and spent long periods in total darkness, on hunger strikes and in solitary confinement. The war resisters who were followers of Gandhi and crusaders for non-violent resistance to evil applied their strategy to ending segregation in prison. Their hunger strike, waged to desegregate dining in Danbury Prison, lasted 135 days before the warden capitulated and Danbury became the first federal facility with integrated meals. When they won, the hunger strikes spread to other prisons. Eventually the entire federal prison system was integrated.

While suffering forced feeding and long bouts of isolation, many war resisters found strength of spirit in their prison experiences and went on to build social movements based on non-violence.

Prison authorities saw COs as a problem population. James Bennett wrote the following about the imprisoned war resisters in his 1943 Annual Report as the Director of the Bureau of Prisons:

The most difficult group of conscientious objectors [is] the political or philosophical objector. He is primarily the reformer with a zeal for changing the social, political, economic and cultural order. Objection to war frequently is only one element of his program....He is more an activist than a pacifist... His motivation frequently stems from an over-protective home or a mother fixation, or from a revolt against authority as typified in the home and transferred to society at large. He is a problem child - whether at home, at school or in prison.

|